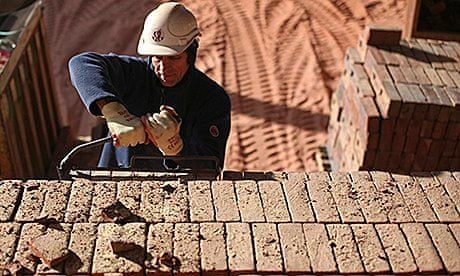

Martin Warner is standing on a pile of nearly one and a half million bricks, stacked several metres high in a vast open shed. Below him pipes of natural gas pump flames into the stack, lighting a fire that will burn day and night for 17 days to bake the bricks at 1080 degrees Celsius, sending the stench of sulphur into the air in billows of steam.

When the whole shed has been set alight, the glowing bricks are left to cool off for a further two weeks. The gas flames are moved on to the next shed, where more "green bricks", moulded from clay are being stacked ready to be fired.

For Warner, chief executive of Michelmersh Brick Holdings, the bustling yard is a welcome sight after the construction sector's deep recession saw brickworks around the country mothballed or closed. Now they are scrambling back into action as the revival in the housing market has led to reports from builders that shortages of bricks and blocks are holding them up. Housebuilder Redrow has highlighted a shortage of roof tiles and skilled workers too.

"There is only so many bricks we can make. We are flat out," said Warner.

It is a picture repeated up and down the country, where many brickworks have kept the fires burning throughout the winter, forgoing the traditional end of year stoppage. Warner's company, listed on the junior Aim market and made up of centuries-old brickworks acquired since the late 1990s, was by no means immune to the downturn. The 300-strong workforce shrank by 100 during the crisis but is back up to 265.

The wider industry went from about 80 brickworks in 2007 to 50 now as demand slumped and manufacturers drove down stocks.

"We have had four years making less bricks than we have sold because there was a stockpile," said Warner.

Then the government's Help to Buy scheme to kickstart the housing market took hold and demand picked up.

"At the time the Help to Buy started picking up in May last year the brick stock reached equilibrium. After five years of grief, of closures, of laying people off, the lights have come on again," said the 60-year-old chief executive, walking around the Freshfield Lane works in Sussex, one of the company's four UK sites. Here wealden clay formed 100m years ago is excavated once a year in early summer and then throughout the year mixed to a special recipe, formed by machine, or sometimes by hand, into bricks for firing.

The whole journey from "quarry to lorry", as Warner puts it, takes 10 weeks. For an industry facing pent-up demand it is a long lead time. At some of Michelmersh's other sites where kilns are used to bake, the process is five to seven days.

The company is investing to make more bricks on the Sussex site. But there is little it can do to cut manufacturing times if it wants the kind of premium bricks that have won it contracts such as supplying the restoration of St Pancras station, says Warner. What he wants to see next is his profit margins recovering after years of rising costs and stagnant prices, an average of 23p a brick for the industry. With haulage, that makes the cost of bricks for the typical 1,000 square foot home £3,000, less than half the cost of a new kitchen.

"We are not all going to be spending loads of money till we get some margin," said Warner, whose own bricks sell for an average of 36p.

For builders, the prospects of supply picking up look slim. Bricks are too heavy to import from far afield, though nearby Belgium and the Netherlands do manage to sell into the UK. Nor does the industry lend itself to new entrants, thanks to the complex manufacturing process, big capital investment required and need for a nearby quarry.

"These are businesses where once they are lost, they are lost," said Warner.

Some believe the shortfall in bricks could have wider repercussions for the economy. A report into the construction industry by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors last week highlighted materials shortages as a drag on the nascent construction recovery. But the lobby group for materials makers says this is simply a return to more normal supply-demand dynamics.

"Pre-recession, housebuilders were used to planning weeks in advance for materials purchasing. After the recession, with subdued activity levels, housebuilders got used to purchasing a few days in advance," said Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association."Now, it may be that house builders have to get back to planning construction materials considerably in advance."

Smaller builders echo that. Nathan Beard, who runs NSJ Building Services in south London, said a breezeblock shortage on a recent job had left his team hanging around for three weeks. Finding tradespeople has been even harder. A few years back people came to sites looking for work once or twice a week; now Beard is calling them.

"We needed an extra bricklayer recently and rang eight that we know and they were all too busy," he said."With plasterers it's the same. We can't get the skills for love nor money. I have 10 or 11 contacts and they are all run off their feet. With carpenters, a few stoped carpenting and had to take on other jobs in the recession. The only ones that are not hard to come by are plumbers, we are saturated with plumbers."